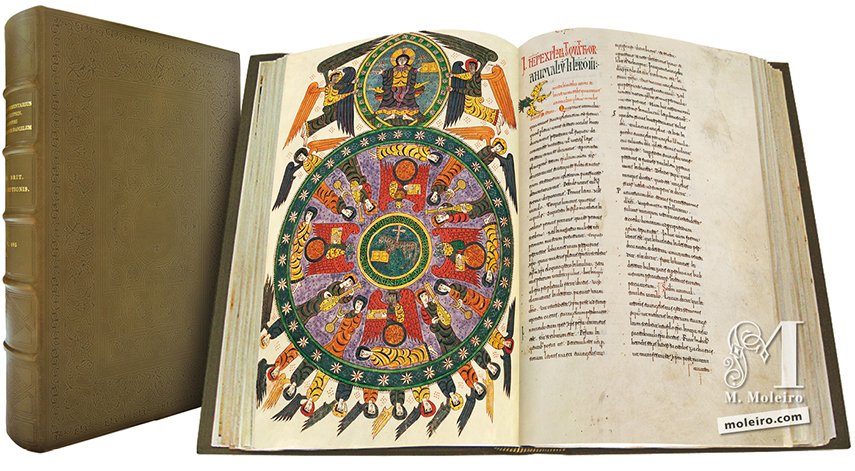

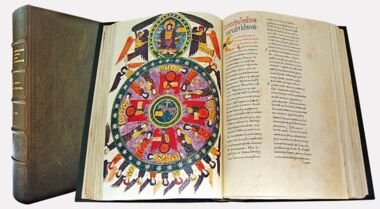

On May 19th 1840, the British Museum, London, bought a magnificent manuscript: a splendidly illuminated copy of Beatus of Liébana's Commentary on the Apocalypse according to St John. The codex had been copied in the scriptorium at the Santo Domingo de Silos monastery and had since had an eventful life.

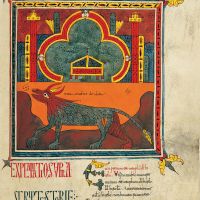

It is surprising that the library in a monastery as ancient as that of San Sebastián in Silos, situated in the south of the province of Burgos and founded towards the late 9th or early 10th century, did not include a book as characteristic as this one until the late 11th century. We are quite familiar with the vicissitudes of the Silos library, its most ancient manuscripts, the rebirth of its scriptorium in the times of its abbot, St Domingo, after whom the monastery was subsequently named, the zenith reached in the times of Abbot Fortunio... However, at no time in the 10th century do we find Silos monks devoting time and energy to copying a beatus, a book which had, since its origin in Liébana in the late 8th century, enjoyed extraordinary prestige. Chance and the interest of an eighteenth-century archivist in Silos, Father Domingo Ibarreta, resulted in three folios from the Santa María la Real church in Nájera being kept in the Silos Monastery. One of these folios, formerly housed in the Cirueña Monastery in La Rioja, dates from the 9th century, making it the earliest extant documentary evidence of the written transmission of Beatus' commentary. It is, furthermore, unique because of its primitive illumination.

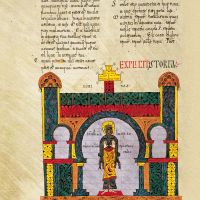

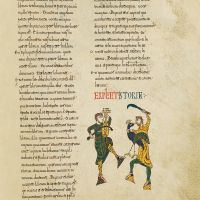

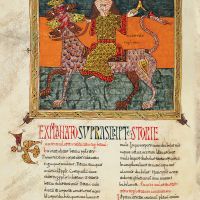

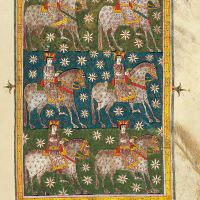

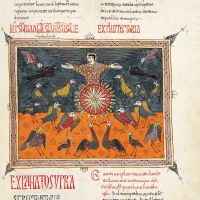

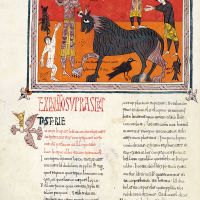

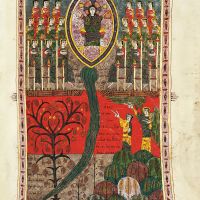

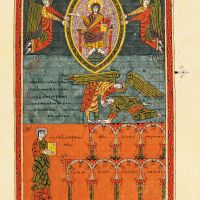

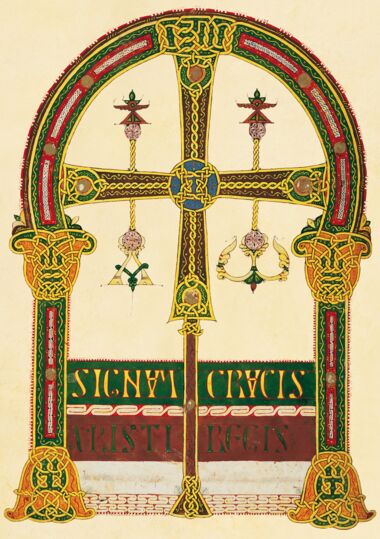

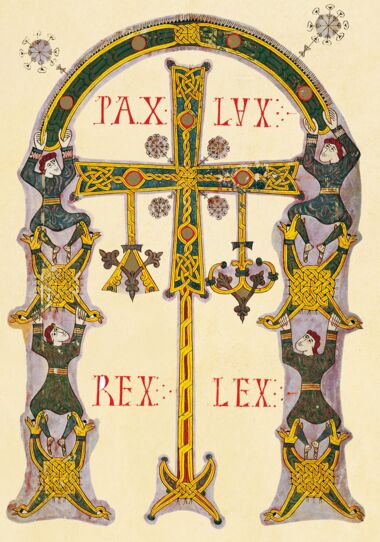

But none of the foregoing concerns Silos directly. In the late 11th century when Beatus' text began to be copied and used less frequently, the Silos monks decided to undertake this expensive task - expensive because this codex required extremely fine parchment, a variety of inks, and silver and gold for its profuse illustrations. What's more, in order to produce a well-finished and well-presented work, skilled calligraphers and illuminators were also necessary. At that time, Silos lacked none of these. The monks Domingo and Muño set to work and at the sixth hour on Thursday, April 18th 1091, they finished the task of copying the text, which may have taken them several months. As was usual, they gave thanks to God for permitting them to finish their work, "Blessed be God for leading me to the door of this work. Blessed also be the king of Heaven for enabling me to reach the end of this book harmless. Amen."

As they themselves remind the reader, the work of a copyist is extremely difficult. "The reader benefits by the labour of the scribe; the latter tires his body and the former nourishes his mind. You, whoever you may be, who benefit by this book, forget not the scribes, so God may forget your sins. For he who cannot write cannot appreciate this work. Should you wish to know, I shall tell you directly: the task of writing destroys the sight, bends the back, breaks the ribs and pains the stomach, causes back-ache and ails the whole body. You, the reader, must therefore turn the pages with care and not touch the script, for just as hail destroys a crop, so does the careless reader erase the text and destroy the book."

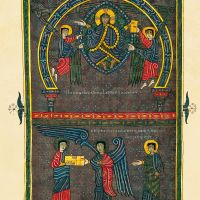

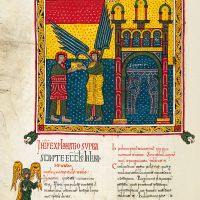

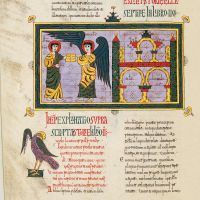

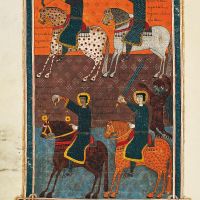

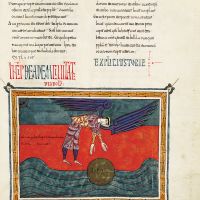

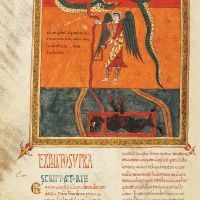

After finishing their task, Domingo and Muño must have passed the still unbound work on to the illuminators who, in the space of more or less one year, were to copy the illuminations from the model into the spaces left blank for this purpose. It was then however that problems began to arise, for unknown reasons. The fact is that when Abbot Fortunio died around 1100, only very few of the miniatures had been completed. Work must have been halted in the following years since the following abbot, Juan, was fortunate enough to receive the fully illuminated manuscript from his prior, Pedro, who must have carried out most of the remaining work. As chance would have it, June 30th 1109, the date when the entire work was concluded, was also the day of the death of King Alfonso VI who had been a notable benefactor of the house of Santo Domingo.

The condition of the manuscript suggests that it was hardly ever used. Almost fifty years after it was finished, a document of such great importance to the community that it deserved to be kept in a safe place, was copied onto one of the blank pages in the codex. The document in question concerned the division between the duties of the abbey and the convent which took place in 1158. A curious reader who had it in his hands in the 14th century marked the passages he found most interesting. Nothing more is known about it from that moment onwards. At some point it was removed from Silos, never to return.

In the 18th century it belonged to Cardinal Antonio of Aragon, who apparently donated it to the San Bartolomé School in Salamanca. After such schools were abolished, it was taken to the Biblioteca Real in Madrid. It may be supposed that this is where José Bonaparte picked it up when king of Spain. He subsequently sold it personally to the British Museum, when he was merely the Count of Survilliers.

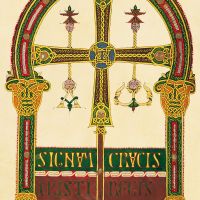

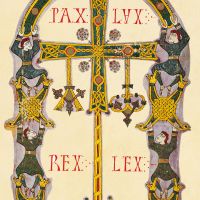

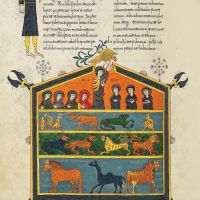

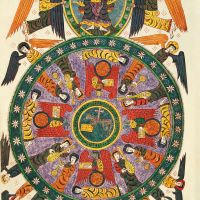

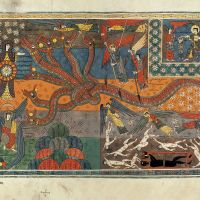

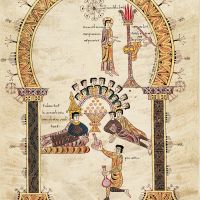

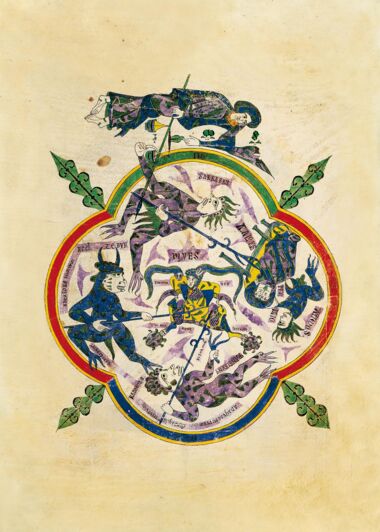

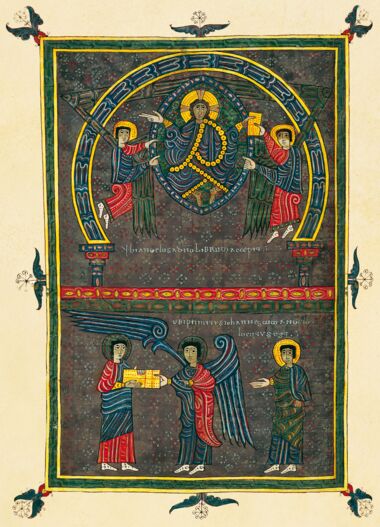

This is basically the story of a manuscript which, although its text poses no particular problems, does contain an iconography that deserves to be studied in depth to accurately determine the different artists involved, their models and influences, their innovations etc. In addition to which, at an unknown moment, it was enlarged by the addition of several lavishly decorated folios taken from an antiphonary, also from Silos, and from a vision of hell, a unique specimen in Romanesque art. A painstaking, palaeographic analysis would however also shed light on the gradual introduction of Carolingian script into the kingdom of Castile for, despite being written entirely in Visigothic minuscule, the codex does contain countless instances of the influence of the new style of script.

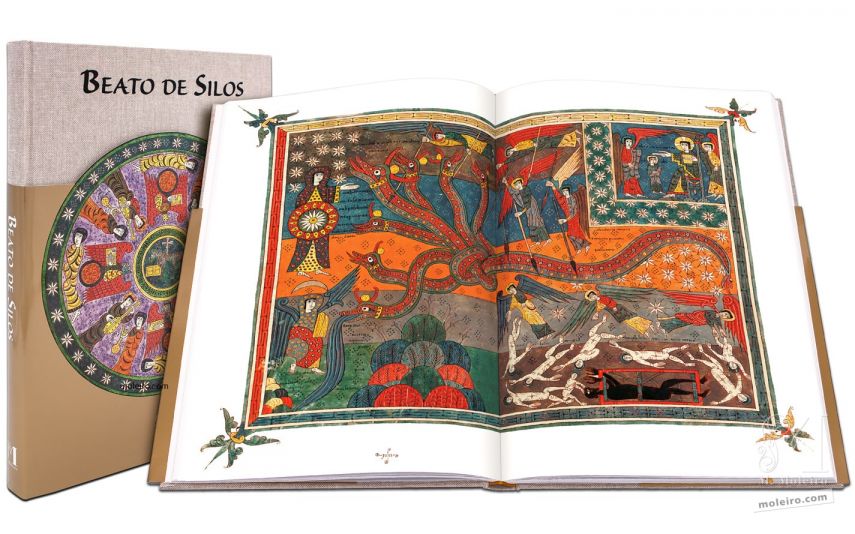

But I believe an aesthetic appraisal of our manuscript to be essential and of even greater importance than these rather erudite considerations. We often forget our emotions when faced by an ancient or medieval work of art and rapidly concentrate on analysing it rationally. But this is was not the intention of Domingo and Muño and, above all, Prior Pedro. The Silos copy of Beatus' work is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful of all those that have survived. Furthermore, it gives the impression that it left its creators' hands barely a moment ago, for nine hundred years of history have left virtually no mark upon it (just three folios are missing from the entire manuscript). The long-awaited facsimile edition of this codex will be of great interest to scholars, but, above all, it will be even more useful to those who love beauty and revel in it.

Miguel C. Vivancos, O.S.B.

Librarian of the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos

Ph. D. in history