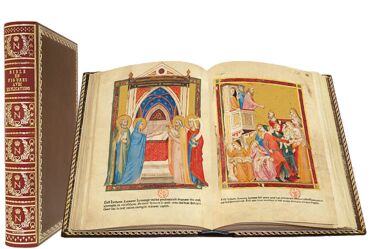

The Bible moralisée of Naples (ms. Fr. 9561) – commissioned by Robert of Naples, also known as Robert the Wise, at the end of his reign and completed in the early 1350s during the reign of his granddaughter Joanna – takes us through more than a century of the dynastic history of France and Italy.

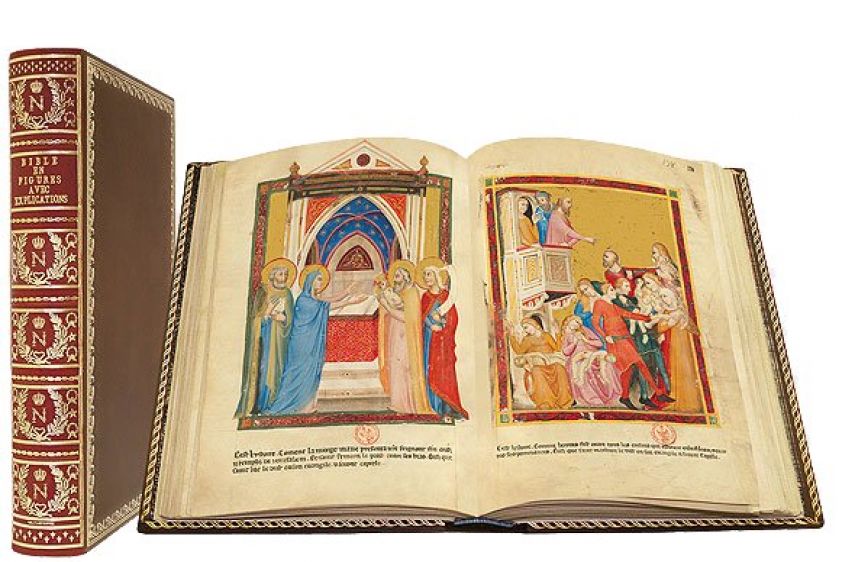

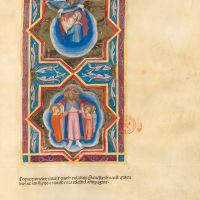

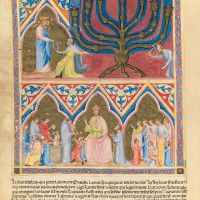

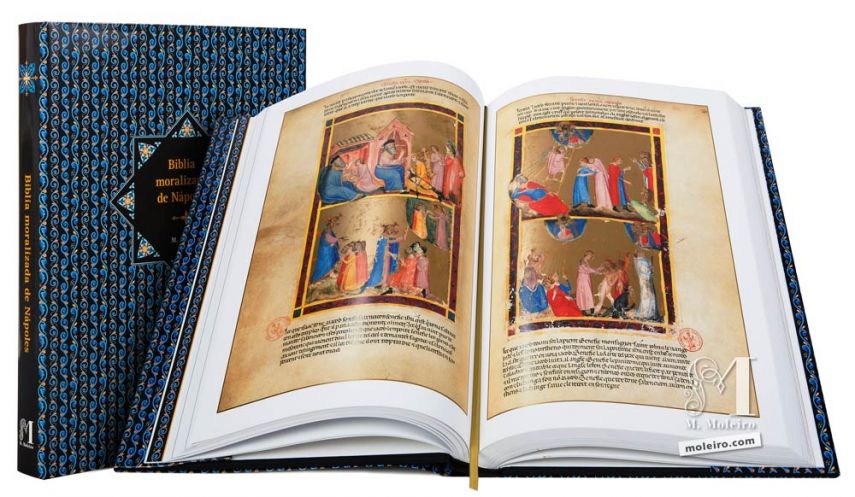

The Bible of Naples was modelled upon a one-volume, French Bible moralisée made in Paris around 1240 which had belonged to Charles of Anjou, the younger brother of St Louis for whom their mother, Blanche of Castile commissioned the Bible of St Louis. The medallions characteristic of these Bibles are replaced here by rectangular paintings that are more typical of the Italian style and even in keeping with the bands of fresco paintings that blossomed from 1300 onwards upon large areas of new buildings. These are some of the prevailing cultural referents that gave the Neapolitan manuscript its characteristic flavour.

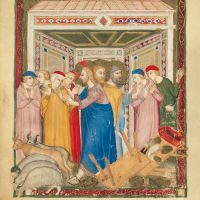

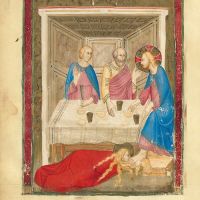

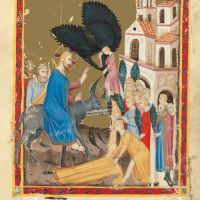

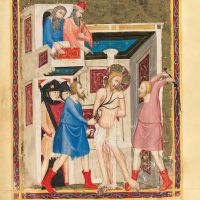

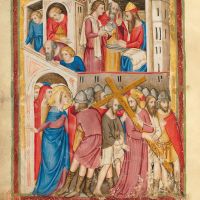

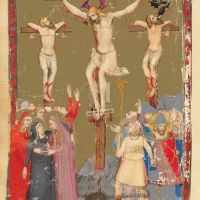

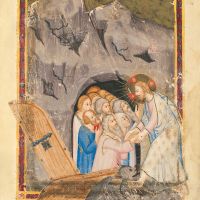

This Bible contains part of the Old Testament (from Genesis to the third book of Judges, ff. 1-112v) together with moralisations and a highly detailed New Testament cycle stretching from Joachim being cast out of the Temple to Pentecost (ff. 113-189v). This Bible is a luxury item with each folio painted on one side only, the flesh side. The manuscript is extraordinary and the exceptional pictorial quality of its illuminations, particularly the 76 full-page paintings portraying the landmarks in Christ’s life and passion, has been emphasised by art historians.

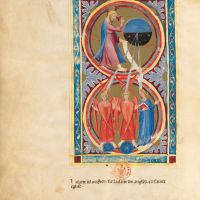

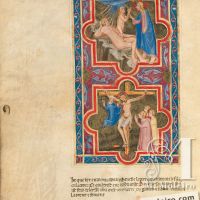

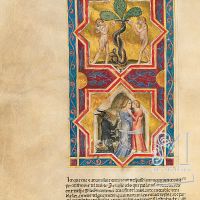

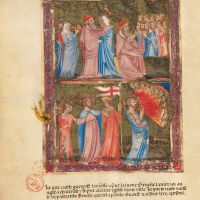

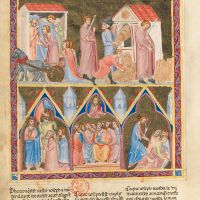

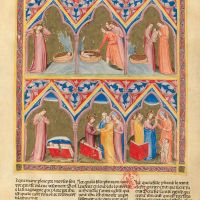

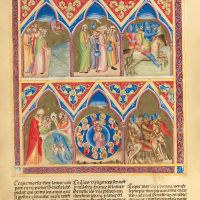

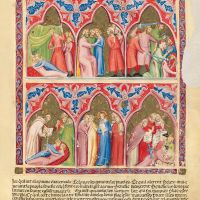

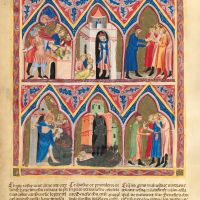

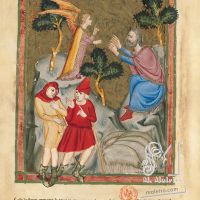

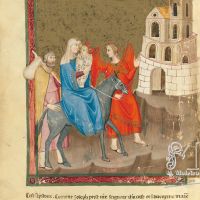

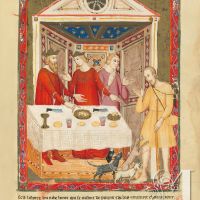

This single-volume Bible features a juxtaposition of two illustrative formulae that make this Bible an exceptional item. The first 128 illuminations belong to the Bible moralisée genre. All the paintings in the Old Testament section, except the full-page frontispiece on folio 1, are framed by borders, many of which have plant adornments, and divided into two registers: the upper one containing the biblical scenes and the lower, their moralisations. The 76 full-page paintings in the New Testament cycle contrast sharply with the preceding cycle, taking us into a different spiritual and figurative realm of mainly Giottesque inspiration. Each illumination is painted on gold-leaf ground and illustrates a single theme, hence the canon of the characters is far wider than in the moralisation part. The cycle begins with apocryphal episodes from the Golden Legend, and the iconographic programme from the Annunciation onwards (f. 129) is inspired by canonical texts. The illustrations as a whole are basically the work of two hands.

What is to be made of this abrupt divide, the about-turn that can be seen between the iconographic programme in the first part of the Bible and the sensitive feel of the second part, totally in keeping with the style of frescoes flourishing in Naples at that time? Everything suggests that production took a long time or was even interrupted for a while and that when it was resumed, the initial project no longer seemed so relevant. This was undoubtedly a period when large paintings provided plentiful sources of new inspiration.

It remains only to determine who commissioned this about-turn and who was charged with carrying it out. The cracks in parts of the painting and the gold leaf applied in others offer glimpses of hands accustomed to the fresco technique. As early as 1969, Ferdinando Bologna suggested that the artist of the Bible’s finest pages be identified with a Neapolitan student of Giotto’s who was also responsible for a cycle of Our Lady’s life made in c. 1335 in the Barrile chapel of San Lorenzo, the sanctuary of a friend and adviser of king Robert.

Manuscript fr. 9561 is the only known Italian copy of a Bible moralisée. It was made for Robert of Naples of the first House of Anjou, a House that descends directly line from the Capetian branch via Charles I, the brother of St Louis and founder of the Angevin dynasty.

The Angevin dynasty established power of a clearly feudal nature in Naples, the new capital of a Guelph and French kingdom. Things got off to a poor start in the reign of Charles I with the lands of the former Italian nobility being ruthlessly pillaged and exploited, causing the invader to be hated and expelled from Sicily. But Charles II, thanks to subtle diplomacy and good government measures, finally bequeathed a peaceful kingdom to his son Robert. The new sovereign soon became a model of justice, wisdom and learning, developing patronage orchestrated as a cultural policy. As a bibliophile, he gave pride of place to books on morals, philosophy, religion, law and medicine. He had them brought from Paris or the rest of Italy and had scribes from France, Lombardy and Tuscany transcribe others books in situ<. The miniaturists are almost all anonymous but Naples must have had several scriptoria and the early fourteenth-century miniaturists were influenced by the innovative art of the Roman painter Cavallini, resident in Naples from 1308 onwards, and subsequently that of Giotto, demonstrated to have been in the capital from 1328 to 1333. Robert of Naples commissioned Giotto to paint frescos in two places symbolising Angevin power: the Palatine chapel at Castelnuovo (the palace) and the Franciscan convent of Santa Clara (the necropolis). The artist was the head of a major workshop consisting of first-rate assistants and several apprentices, many of whom were undoubtedly from Florence and Assisi, cities that also had large workshops in the 1330s. Some ten years after his death (1337), when the second part of the Bible moralisée was being made, the master’s legacy, perpetrated and modified by his followers including Maso di Banco particularly, was perfectly assimilated by his Neapolitan students too.

Robert cleverly hired the best artists of his times. He commissioned them to design ambitious series serving to legitimise and promote the royal household underpinned by a veritable “image policy”. The Bible moralisée probably belonged to this sphere of self-promotion of the dynasty of a family with two saints to venerate amongst its members since then: Louis of Toulouse and the Capetian ancestor, Louis of France, for whom another Bible moralisée was made in Paris. This work, probably sought after by Robert, confers upon the Neapolitan copy the symbolic status of a reliquary item, evidence of an illustrious family genealogy and its legitimate claims.

This manuscript is one of the rarest and masterful examples of truly Neapolitan painting, a paradoxical synthesis of the finest artistic trends from the time before the homogenisation of international Gothic.

King Robert ruled Naples from 1309 to 1343.