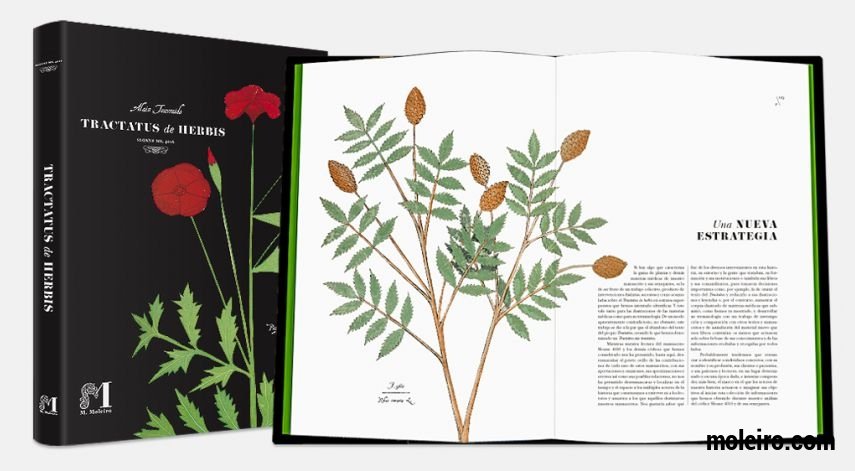

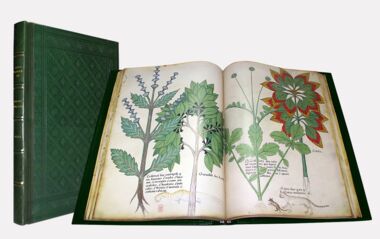

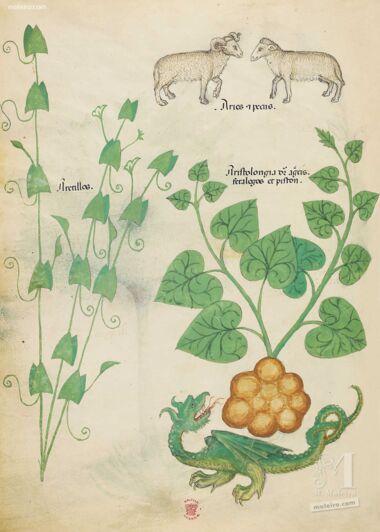

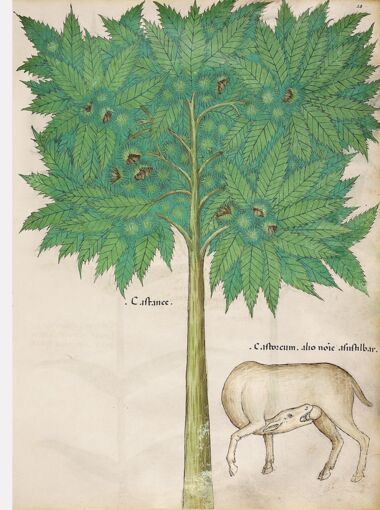

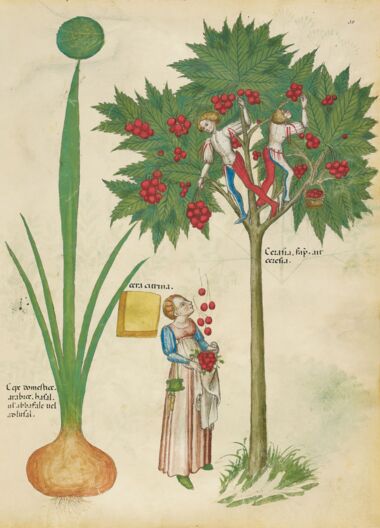

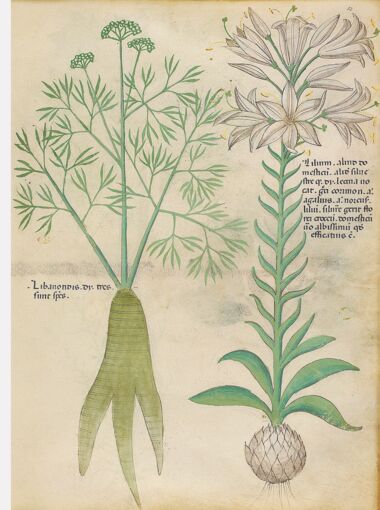

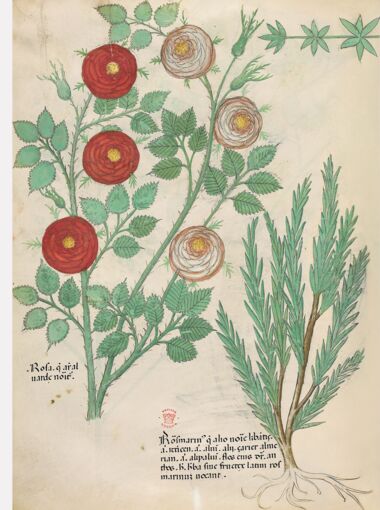

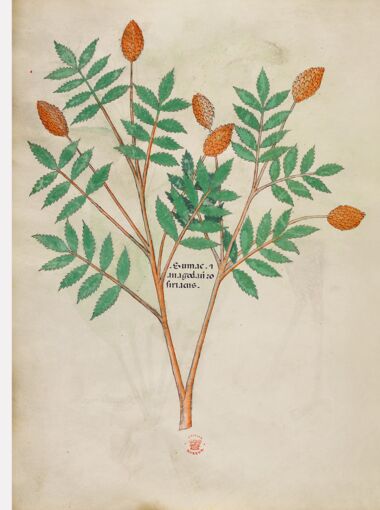

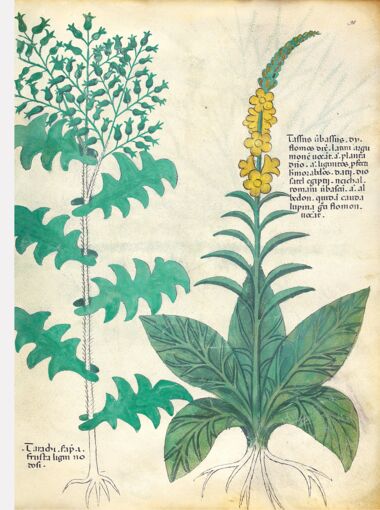

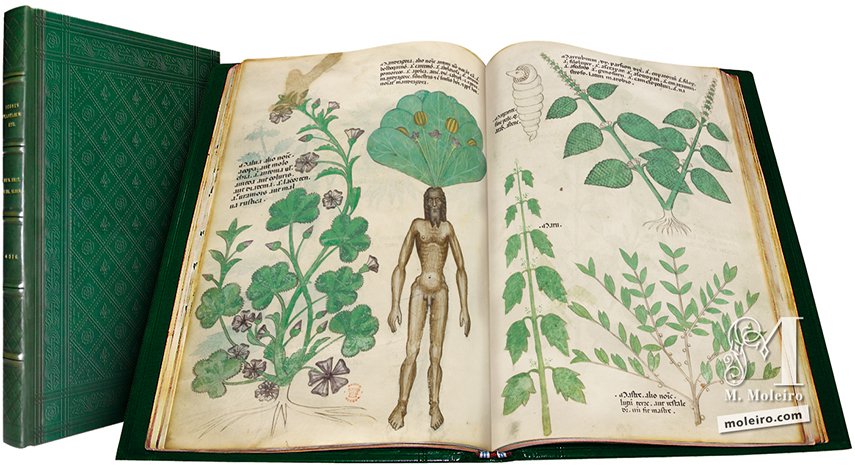

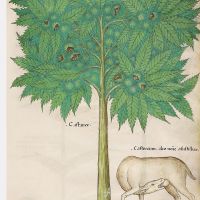

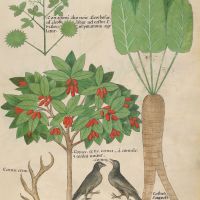

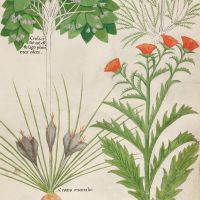

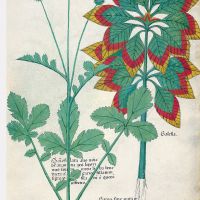

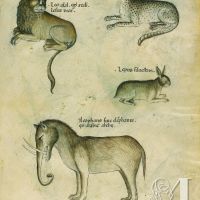

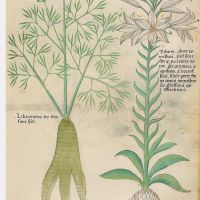

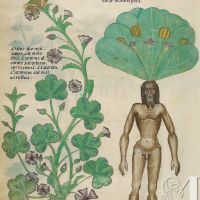

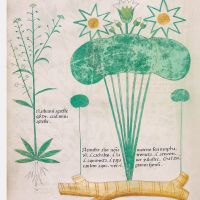

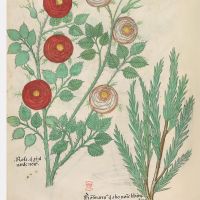

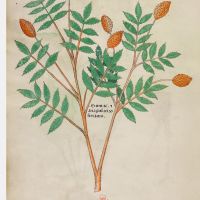

In the Middle Ages, medicine was undoubtedly the scientific realm influenced most by the many cultural elements that contributed to shaping society. Its Greek foundations were added to by Latin, Byzantine, Arabic and Mozarabic contributions and others from further afield that were transmitted by cultures bordering on the western world. As a result, each medicinal plant had as many names as the cultures using it to make remedies. But the variety of names used for a single plant in different cultures sometimes led to confusion. To avoid this risk, dictionaries were produced and botanical albums too, featuring pictures of the plants and other simples used in everyday therapeutic practices together with the various names they were called by the different peoples that comprised medieval society. The Tractatus de Herbis, codex Sloane 4016, currently in the collections at the British Library is one such book enabling the different names of these plants to be linked to the plants themselves. This helped avoid confusion and the disastrous consequences of giving a patient a simple other than the one prescribed by the physician.

Towards a better understanding

The Middle Ages have a poor reputation, as its name suggests. It is a poorly understood era boxed in between two periods of supposed splendor ’ the Ancient World and the Renaissance. The many synonyms and expressions used to define it only confirm and add to this reputation: the "medieval interval", the "Dark Ages", the "medieval obscurity" and many more. The ten centuries from the rise to the fall of Constantinople, from 324 to 1453 AD, which define the Middle Ages, are far from obscure. On closer inspection, many different populations entered onto the scene of history and played a major part, different forms of art appeared, economies, farming activities and agriculture were transformed, and new models of government and new political entities came to light. All of these had their own highs and lows but are far from being a kingdom of darkness, as the history that is focused on the Ancient World or the Renaissance might have us think.

Among all the innovations of the Middle Ages, the many languages brought by new arrivals along the perimeters of the Mediterranean and on the continent cannot be overlooked. The international languages, Latin, Greek, Arabic, served to unify this multitude of people in one area or throughout the medieval world, at one time or other, or even throughout the era. Nonetheless, many other diverse languages were spoken which might at times have created a confusion reminiscent of the tower of Babel or given rise to a lack of mutual comprehension due to linguistic particularities. Certainly, the borrowings from one language to another, especially along the frontiers, allowed for people to understand each other. While this osmosis facilitated communication, certain words and expressions resisted change, some probably even up to our day. Plant names are one such example. It is difficult to absorb new names from one culture to another. Those born in the countryside, as was the case for most people at the time, knew plant names by their traditional local name, and certainly not by their scientific name, as might be the case for their urban contemporaries. But even if some names came to reflect cultural exchanges as a result of contact with other people, they often remained tied to deeply rooted traditions which did not facilitate communication.

In the meantime, it was essential to be understood, especially as plants played a fundamental role in living, not only as a food source but also as medicines and as means of maintaining health. The doctores and physici who cared for patients could well have written multilingual dictionaries, but these would have been cumbersome and would not have permitted easy access for quick reference. A more efficacious solution emerged: to compile illustrations of plants with their names in various languages. In short, a sort of visual aid developed which, more precisely than words, furthered understanding and exchange of knowledge. From their role as interpreters, so to speak, these illustrated works, void of text, evolved in their mission and transformed botanical literature. So long as the books had the plant names in all the different languages, it was no longer necessary to illustrate the books dedicated to plants and their use. The new references could now be consulted and used by readers of any language.

Such is the Tractatus de Herbis, codex Sloane 4016, a book without narrative text, containing only captions, so that it could be used by all readers. It was a book connecting the populations of the Middle Ages thanks to its visual nature, a book that was based on image. This was a manuscript that allowed for transcending differences, in short, a book that shows us that the Middle Ages were not an obscure era, but one perfectly capable of mastering visual communication within a modern framework.

Alain Touwaide

Smithsonian Institution

![f. 98v: Terra sigilata; animal testicles; yew; [Badger]; hemp-nettle; turpentine; turtle](/vista/estaticos/formateadas/TH-th6-200-200.jpg)