In the latter half of the 16th century, the Ottoman Empire was the largest and most powerful in the world. Its domains, stretching from Budapest to Baghdad, from Oman and Tunis to Mecca and Medina near the Red Sea, encompassed cities as great as Damascus, Alexandria and Cairo. The Turks were at the gates of Vienna and controlled the Silk Route, the Black Sea and the eastern half of the Mediterranean. The sultan governed the empire from Constantinople, where architects, painters, calligraphers, jewellers, ceramists, poets, etc, were at his service with his court and harem. Learned, sybarite sultans, such as Süleyman the Magnificent and his grandson Murad III, became great patrons of the arts and were responsible for the spectacular growth of the workshops in the Seraglio that gave birth to an original Ottoman artform that shook off the Persian influence still lingering in the 15th century.

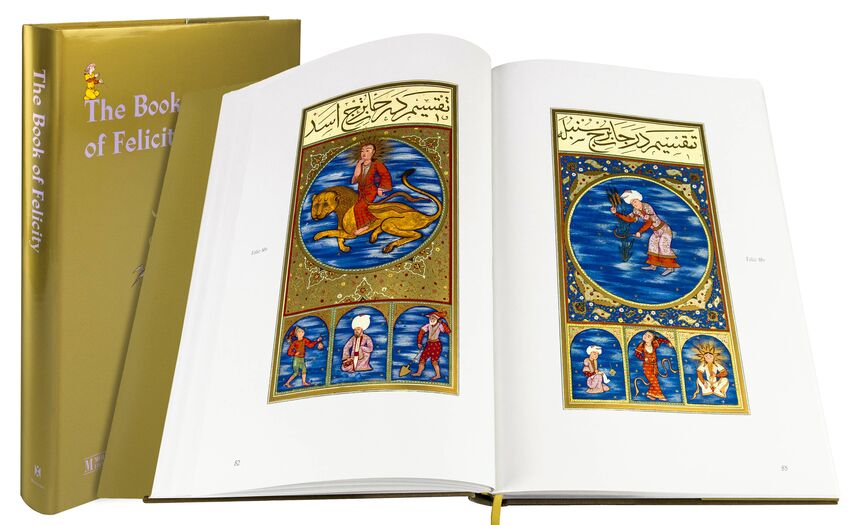

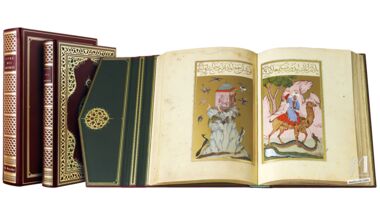

The 16th and early 17th centuries were the most fertile period of Turkish-Ottoman painting, with the reign of Murad III (1574-1595) being particularly prolific in beautiful works of art, such as this Matali’ al-saadet or Book of Felicity by Muhammad ibn Amir Hasan al-Su’udi.

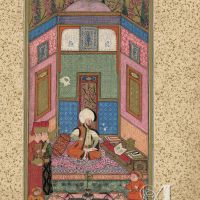

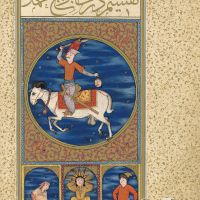

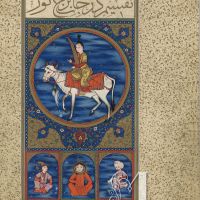

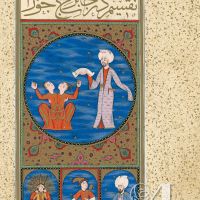

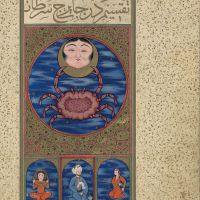

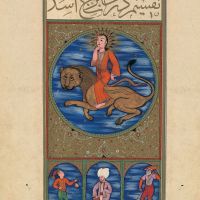

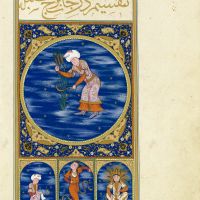

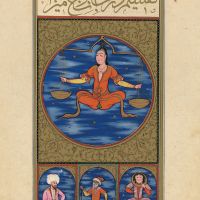

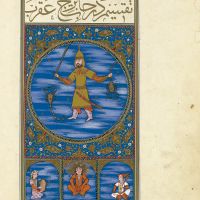

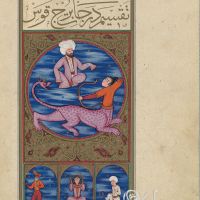

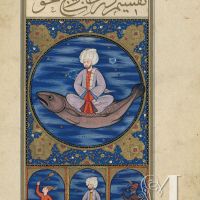

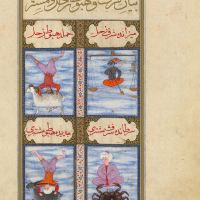

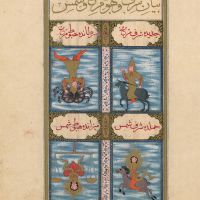

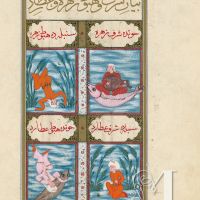

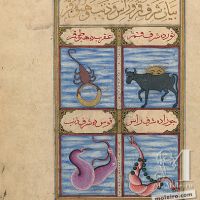

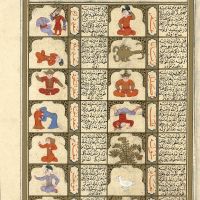

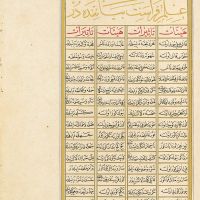

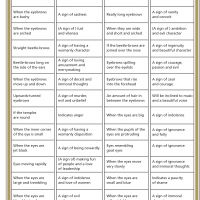

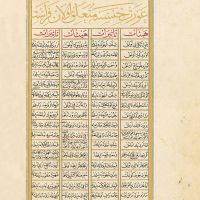

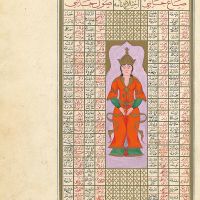

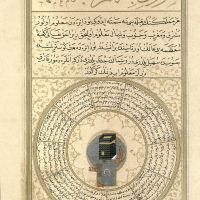

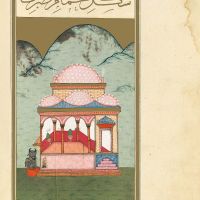

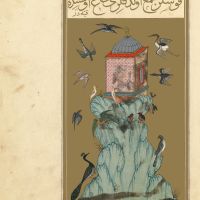

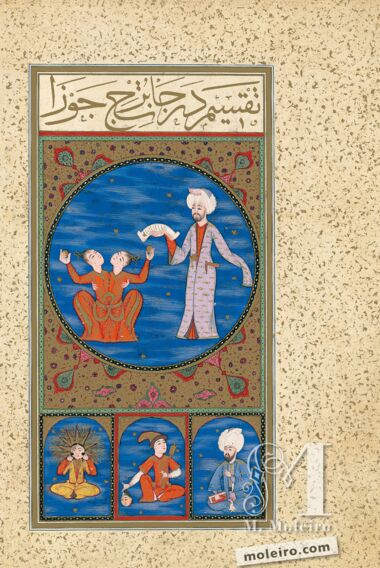

This Book of Felicity – which the sultan himself, whose portrait appears on folio 7v, ordered to be translated from the original Arabic – features descriptions of the twelve signs of the zodiac accompanied by splendid miniatures; a series of paintings showing how human circumstances are influenced by the planets; astrological and astronomical tables; and an enigmatic treatise on fortune telling.

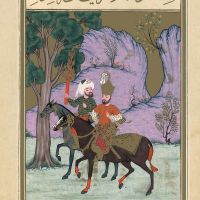

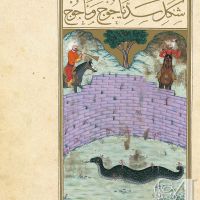

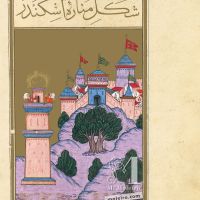

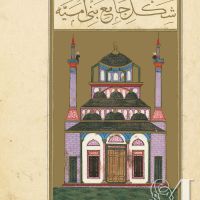

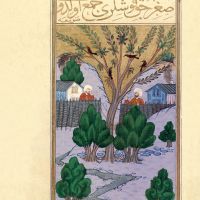

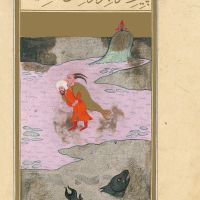

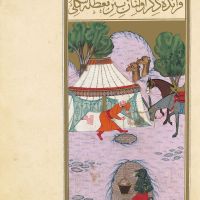

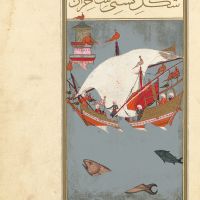

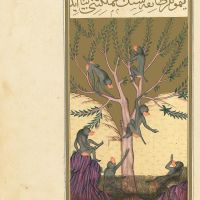

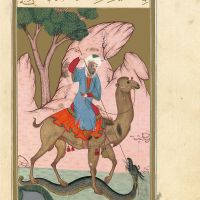

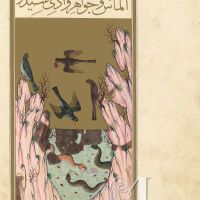

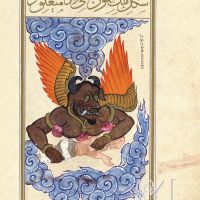

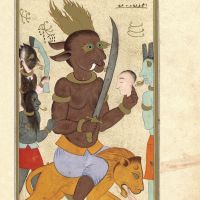

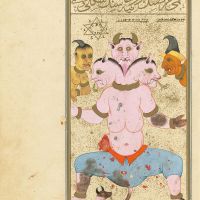

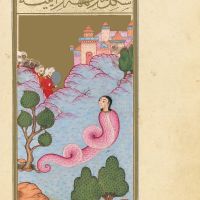

The oriental world unfolds before our very eyes in each miniature: mysterious characters in peculiar poses, exotic, brightly coloured garments, luxurious mansions and sumptuous palaces, muezzins in the minarets of mosques calling the faithful to prayer, elegant horsemen riding their stylised horses with lavishly embellished trappings. Countless exotic animals fill the pages of this manuscript: exuberant peacocks, extraordinary sea serpents, giant fish, eagles and other birds of prey, swallows, storks and other birds drawn in an elegant, stylised manner revealing considerable influence by Japanese painting. There is also an entire chapter on the monsters appearing in medieval, Turkish imagery, brimming with menacing demons and imaginary beasts.

All the paintings seem to be by the same workshop under the guidance of the famous master Ustad ‘Osman, undoubtedly the artist of the opening series of paintings dedicated to the signs of the zodiac. ‘Osman, active between around 1559 and 1596, directed the artists in the Seraglio workshop from 1570 onwards and created a style, adopted by other painters at the court, characterised by accurate portraits and a magnificent treatment of illustration.

Sultan Murad III was completely absorbed by the intense political, cultural and sentimental life of the harem. He had 103 children, only 47 of whom outlived him. Nevertheless, Murad III, who held illuminated manuscripts in greater esteem than any other sultan, commissioned this treatise of felicity especially for his daughter Fatima.

The manuscript was brought from Cairo to Paris by Gaspard Monge, the renowned geometer and count of Péluse, and deposited in the library on behalf of Napoleon Bonaparte.