Description

It belonged to St. Louis IX, King of France, who gave it to Alfonso X the Wise.

It was copied and illustrated between 1226 and 1234 in Paris.

Life in the Middle Ages is revealed through the images presented in this codex.

Biblical texts and glosses blend with the iconography to create an unalterable whole.

Unique monument of book illumination that constitutes both unlimited information for historians and a boundless source of pleasure to the senses.

The Bible of St Louis

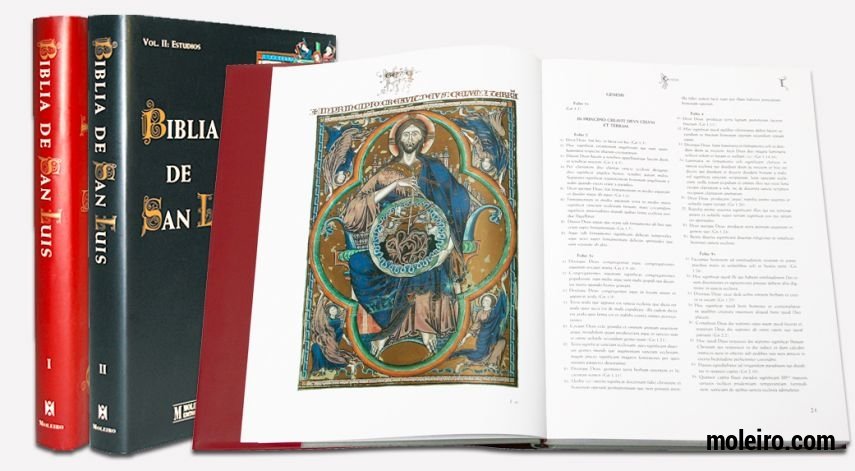

The Bible of St Louis of Toledo Cathedral is a truly outstanding item within the rich heritage of Toledo Cathedral. This Bible moralisée written in Latin is so extraordinarily beautiful that it is also known as the "Rich Bible of Toledo".

The earliest references to this work date back to the codicil and testament of Alfonso X the Wise, king of Castile, which describe it as being a "historiated Bible in three books given to us by the king of France" and "one of the most noble items belonging to the king". The Bible of St Louis to which Alfonso X the Wise refers is in all likelihood the one housed in Toledo Cathedral. The studies made of the different aspects of this Bible together with the analysis of its contents enable the date of its composition and the period in which it was copied and illuminated to be determined very approximately. These tasks were completed between 1226 and 1234. This vast, highly accurate and meticulous work required the patient dedication of many experts in the widest possible fields covered by theologians, copyists and illuminators.

This codex was produced for kings for educational and informative purposes, and also as a pedagogical tool in the education of the future king of France. Over the last eight centuries the Chapter of Toledo Cathedral has dedicated the utmost care to conserving and housing this bibliographic gem which can be described in its own merit as unique and which draws gasps of admiration from everyone who has the chance to see it.

Increasingly large numbers of scholars are interested in researching into this endless source of culture brimming with so much doctrinal wealth typical of the 13th century. The number of requests the Chapter receives from persons seeking direct access to the Bible of St Louis in order to study and conduct research on a great many subjects, increases every day. The reasons for such interest vary considerably: some concern biblical and theological aspects; others are intrigued by artistic and ornamental considerations; and yet a third group includes those who focus their research programme on a historical perspective.

The Chapter of Toledo Cathedral is aware of the need to be sufficiently open to permit access to anyone interested in investigating the Bible of St Louis. It is equally aware of its duty to keep this unique treasure in the best possible condition and to conserve what has been looked after for so many centuries with such zeal, by providing this unique item amongst the Cathedral's treasures with the maximum security and custody.

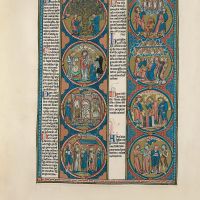

These are the reasons which drove the Chapter to produce a facsimile edition of the Bible of St Louis. The venture appearing today deserves our applause. After approaching different publishing houses, the project was finally entrusted to M. Moleiro Editor. The outcome is undoubtedly of benefit to us all. I would finally like to take this opportunity to express my satisfaction and also to congratulate all those whose efforts have made this facsimile edition of the Bible of St Louis possible. I am well aware of all the virtually anonymous people in the background who have dedicated so much time and enthusiastic effort to achieving this arduous and difficult task whose marvellous result cannot be praised too highly.

In producing this facsimile, the Chapter has rendered a great service to culture in general and assistance to the many libraries and individuals interested in this subject by providing a great opportunity to make use of and complete this reproduction: a remarkable tool enabling a multitude of research and academic projects to become reality.

Francisco Álvarez Martínez

Cardinal Archbishop

The Bible in Castile

The first documented record about the Bible of St Louis appears in the will and testament of Alfonso X the Wise of Castile. This will, written in 1282, describes a Bible "of three illuminated volumes given to us by King Louis of France." This short but precise description is sufficient to lead us to believe that he was referring to the same copy that resides today in the treasury of Toledo Cathedral. In addition, this particular copy, divided into three books or volumes each replete with ornate illustrations of the biblical tales and originally owned by King Louis IX of France is surprisingly similar to the Rich Bible of Toledo. Furthermore, the will explains that Louis IX gave the codex to Alfonso X as a gift. This valuable piece of evidence clarifies the mystery surrounding the presence of this bibliographic gem in Castile.

In his will, Alfonso X expressed great appreciation for this Bible classifying it as one of the "noblest possessions belonging to the King." In his testament of 1284, he also alludes to the Bible as one of "the things we had in Toledo that were taken" during a robbery of the royal holdings. The king describes his regret at having lost one of "the rich and noble things that belonged to the kings". This entry, in addition to the similar phrase written in his will, attests to the fact that this invaluable piece of art was destined for the exclusive use of royalty.

An Extraordinary Bible

The Bible of St Louis is one of a small group of Bibles copied in the 13th century for members of the French royalty belonging to the Capetian dynasty ruling at that time. It is a peculiar type of biblical book without precedents in the tradition of European scriptoria, and is lavishly illuminated in keeping with the rank of its owners.

These bibles were usually known by the more modern name of Bibles moralisées and were few in number, as mentioned earlier, due to the high cost of producing them. The most obvious feature of these books is their incredible lavishness and splendour. Their external appearance is so exceptional that one immediately realises that their owners could only be the most high-ranking persons in medieval society. This was indeed the case: these Bibles were made for the use of kings alone.

The huge number and quality of their illuminated storia catch the reader's attention from the start. The singularity of these Bibles is demonstrated mainly in two aspects: their codicology and texts.

From the viewpoint of the work as a book, we must admit that everything in it is extraordinary. The persons who commissioned it envisaged a project on a vast scale, far larger than any usually produced by book craftsmen. We could even say that everything was sacrificed in the name of magnificence. Some of the requirements in terms of grandeur and splendour imposed by the project forced those working on it to breach many of the rules laid down in the ateliers of copyists and illuminators.

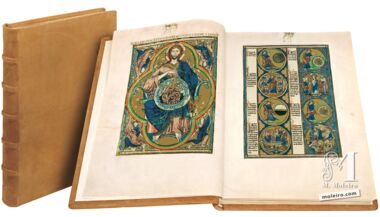

Whilst not of the same size as the ancient Atlantic Bibles, it has nevertheless a very large format and an exceptional number of folios, all of the finest quality. The enormous amount of decoration made it impossible for the parchment folios to bear so much paint and gold on both sides since the pigments would have soaked through to the other side, causing the sheets to crumple. The only solution was to leave one side of each folio blank.

The most surprising aspect is that the sides used for the text and images were not the flesh sides, which are whiter, but the hair sides. The reason for this was that the roughness of the hair side enabled the pigments to adhere much better.

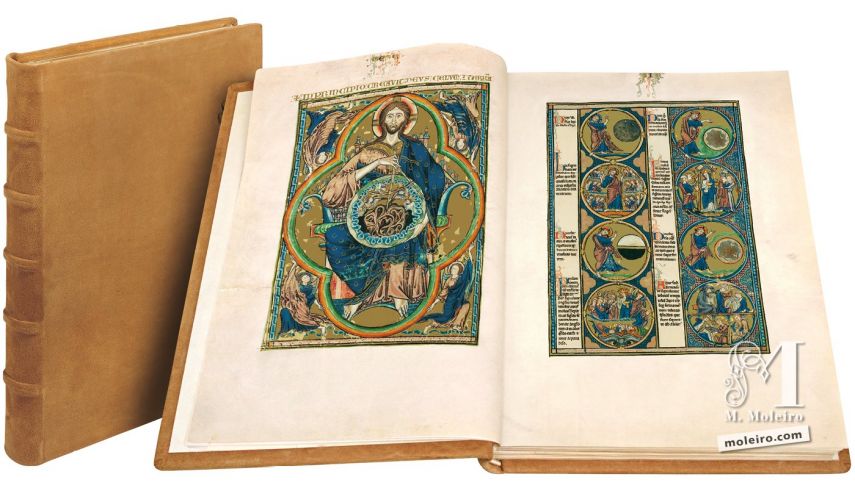

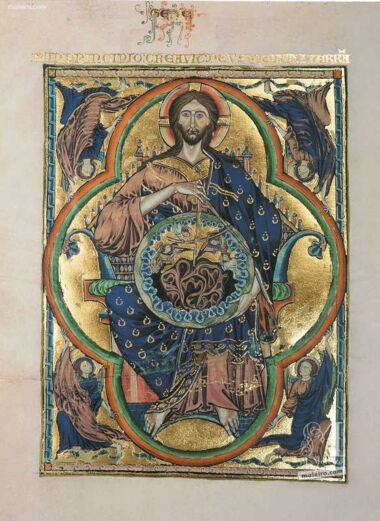

The entire Bible is presented as a totum continuum, opening with a large, illuminated page (God, the Creator of the Universe) and ending with a full-page miniature (Queen Blanche and her son Louis at the top and the codex craftsmen at the bottom), an indication that the book was designed as a single unit. The completed quires were gradually accumulated and in the end it was necessary to split the work into three volumes: a final operation which was not envisaged or allowed for originally. The division was done in a rather arbitrary fashion as revealed by the places where the work was divided into volumes.

Looking at the work from the viewpoint of its texts, it can be seen that this book does not coincide completely with our notion of what a Bible is. First of all a careful analysis of the text shows that it is not a complete Bible but a selection of biblical texts, with many others missing. Exactly half of the text does not belong to the Bible but consists of commentaries written by anonymous theologians. No biblical text stands alone: each one is accompanied by an authorised commentary. These short theological texts were so important to those in charge of the work that they were given the same treatment as the biblical texts themselves: both types of texts were glossed iconographically by an illuminated storia along the side.

Hence the texts in this work belong to both the Bible and theology in equal parts. The foregoing also demonstrates that, in this respect too, the Bible of St Louis is a very particular Bible, an utterly singular work.

A Bible for the King

Alfonso X wrote in his testament that the work was made for use of kings, but the crucial question remains, why did the King of France and his mother need it’ Was it just a whimsical possession’ There is no documentation in the royal records of France about the purpose for which the Bible was made. However, we cannot reject the theory that the Bible had some utilitarian purpose for the people who used it in the Middle Ages. Books were made to be used as a vehicle of learning and information. According to this theory, books circulated amongst the people who had a use for it. The fact that the Bible was made during the time that the French prince was in his

school years suggests that it was made to serve as a pedagogical instrument to complement the education of the future monarch of France. One might even venture to say that it was given to Alfonso X the Wise in order to educate his children and grandchildren.

Composition

From the last illuminated folio, we can determine the timeframe in which the codex was copied and illuminated. Louis IX of France was born in 1214 and took the throne in 1226. In 1234 he married Margaret, the daughter of Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Provence. Given that Saint Louis appears in the portrait as the reigning king but is still unwed, we can deduce that the Bible was completed between 1226 and 1234.

Iconography

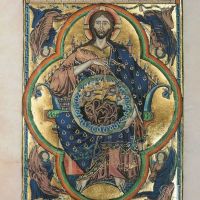

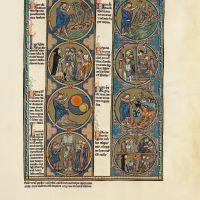

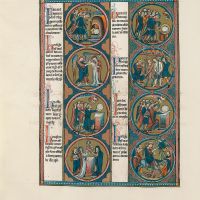

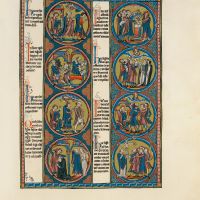

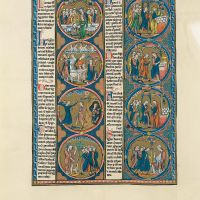

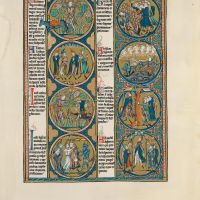

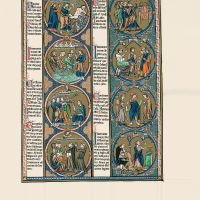

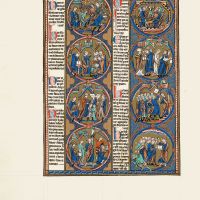

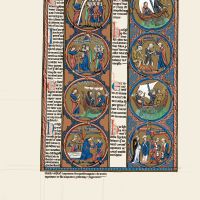

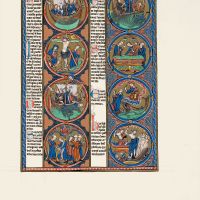

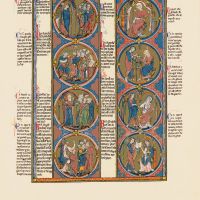

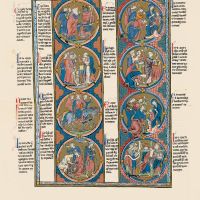

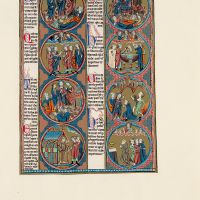

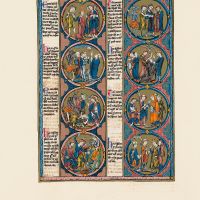

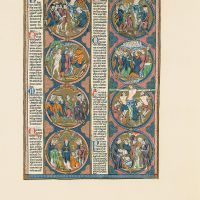

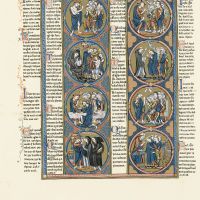

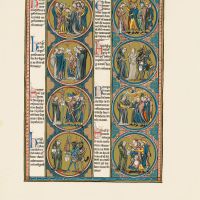

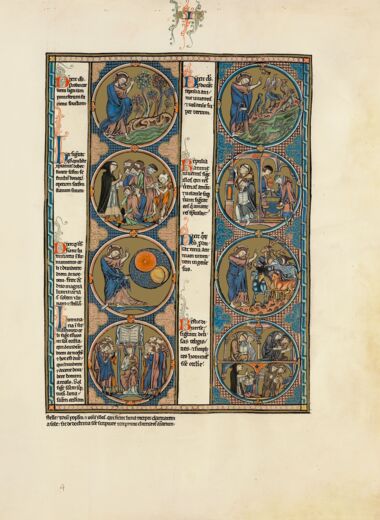

The biblical text, commentaries and iconography form a complete picture on each folio. Each page contains a rectangular space that is divided into four vertical columns of uneven width. Two columns contain text and two contain decorative illustrations. The columns with text are narrower than the decorative columns and are framed by a thin border. Each of the decorative columns contains four richly adorned medallions, totalling eight per page. Hence, the three volumes contain some 5,000 miniatures. The abbreviated biblical text is followed by a series of commentaries that include historical allusions, allegorical tales, moral assertions and mystic references. The Bible is famous mainly for its extravagant iconography. Each medallion reproduces the corresponding scene described in the biblical text. The artists employed a wide range of colours (blues, greens, reds, yellows, greys, oranges and sepia) upon burnished gold grounds. The overall composition brims with highly expressive artistic and technical resources. Most of the medallions contain a single scene although some are split in two by a cloud, arch or straight line. The illustrators used the moralistic commentaries to include criticisms of society from a monastic viewpoint. This Bible contains representations of life in the first half of the 13th century: men, social groups, their vices and virtues, apparel, customs, beliefs, games and ideals. The images in this Bible constitute a portrayal of medieval life.

The Workshop

Although there are no historical sources that document the actual place of manufacture, the Bible of St Louis was undoubtedly made in Paris. It can be assumed to have been made there because Paris was not only the capital city of the kingdom and courts but also the location of the most renowned school of theology in Europe. It was against this background that the demand for the production of Bibles – particularly highly elaborate, illuminated Bibles – focussed on the city and reached its peak there, monopolizing the trade to such an extent that other cities were unable to compete with the quantity and quality of the books produced in the capital. The Bible of St Louis was made during one of the most glorious periods of Parisian scriptoria.

Judging by the importance of this Bible and the social standing of its owners, one can imagine that the workshop selected to produce it was also one of great prestige. Its name, however, remains a mystery.

The Authors

To date, it has not been possible to locate any documentary evidence of the names of the authors. The only clues we have lie in the work itself, in the large miniature at the end of the last quire. Until new documents are discovered, answers to the authorship question must be sought in the realms of what is suggested by the illumination on the last page.

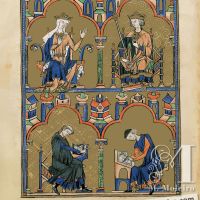

This page depicts four figures, two larger ones in the top scene and two smaller ones in the bottom scene.

The main section is occupied by two members of French royalty. The female figure, whilst having no attributes to identify her definitely, has been interpreted as Blanche of Castile, the mother of Louis IX. Seated on her throne and garbed in her regal cloak and white veil, she addresses the young monarch in an active, conversational pose. The king listens respectfully, holding the gold bull hanging upon his chest in his fingers. The pose of each figure suggests that the queen is dedicating the completed Bible to the young king. If this is the case, then it was the queen who commissioned and paid for the work. Her son, for whom it was made, receives it.

The bottom section features persons literally of lower rank. The subordinate position of these two people is obvious because their representations, smaller in size, are situated lower down, meaning that their responsibility in the work was of a subordinate nature. The first figure is a cleric sitting on his bench giving orders to a copyist and supervising his work. Since this cleric is dressed as a religious, we can immediately rule out that he was of episcopal rank as has been suggested elsewhere.

This figure’s appearance suggests a cleric belonging to a religious order deliberately depicted without any characteristic traits. I am of the opinion that this ambiguity is due to the fact that copyists were directed by members of more than one religious order.

If this interpretation of the end miniature is accepted, then the authorship question of this Bible is resolved, at least partially. The large illuminated page suggests that the four figures depicted on it shared the authorship and that each one took a proportional part in certain aspects. In other words, the Bible was the fruit of joint authorship. The queen was responsible for the initiative of the project, its sponsorship, financing and the right to establish the basic guidelines governing the work. In certain respects the king for whom the book was commissioned was also involved in the authorship. The book was meant for him and was designed bearing him, his Christian education and political benefit as king in mind.

Also included in the author category are the clerics carrying out the instructions received, applying them and directing the craftsmen working on the book. As mentioned earlier, they were probably a group from different religious orders perhaps consisting mainly of members of the Franciscan, Dominican and the two mendicant orders. They were responsible for designing the book in general with its characteristic features according to the instructions they received.

The copyist portrayed in the final miniature also represents the group of craftsmen skilled in bookish arts who played an active part in it. Just leafing through any volume of this Bible is enough to realise that many different hands were involved in the task of copying. Likewise, more than one illuminator was involved in the decoration. They played a leading role in the creation of a work of incomparable beauty deservingly admired and appreciated by the most educated monarchs of its epoch.

Ramón Gonzálvez Ruiz

Canon Archivist and Librarian

"Near Original" reproduction

The long awaited reproduction of the Bible of Saint Louis is important for its historical and artistic value. By making it available to the public, the publisher, M. Moleiro Editor, renders an invaluable service to those who study history and the history of art as well as those who appreciate the great bibliographical works of the world.