Description

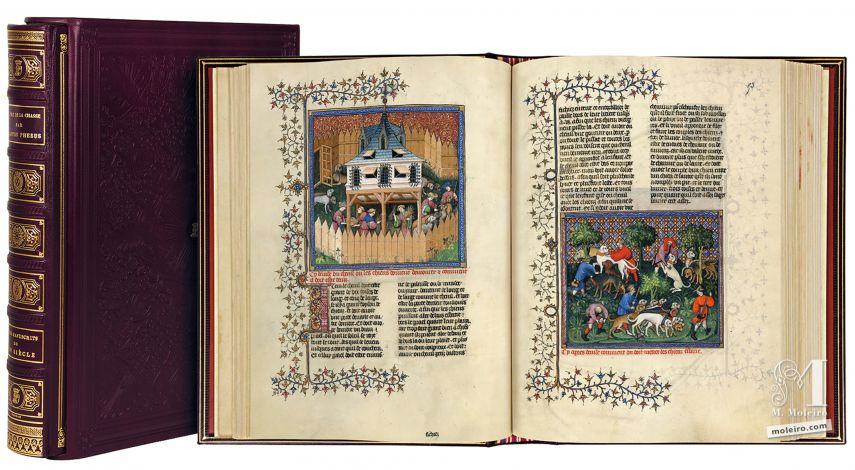

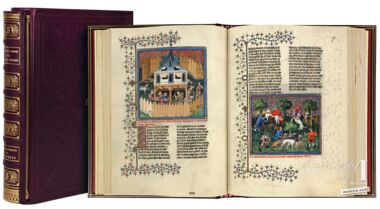

Livre de la Chasse, by Gaston Fébus

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

History of the manuscript

In the course of its existence, the Livre de la Chasse (Book of the Hunt) has changed hands many times. It once belonged to Aymar de Poitiers (late 15th C), and Bernardo Clesio, bishop of Trento, who gave the manuscript shortly before 1530 to the archduke of Austria, Ferdinand I of Habsburg and brother of Charles V. In 1661, the marquess of Vigneau gave the Livre de la Chasse to Louis XIV (reign 1643-1715) who sent the manuscript to the Bibliothèque royale. In 1709, it was removed from that library and came into the hands of the Dauphin and duke of Burgundy who apparently deposited it in the Cabinet du Roi. In 1726, the manuscript reappeared in the count of Toulouse’s library at Rambouillet château and upon his death, was inherited by his son, the duke of Penthièvre. It subsequently belonged to the Orléans family and then Louis-Philippe I who deposited it in the Louvre in 1834. Finally, after the 1848 revolution, it entered the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The book

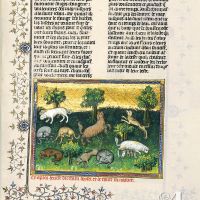

The Livre de la Chasse was written or, to be more precise, dictated to a copyist, between 1387 and 1389 by Gaston Fébus, count of Foix and viscount of Béarn, and dedicated to the duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold. The count had a difficult temperament and an eventful life, and was a great hunter and particularly fond of hunting and books on hunting and falconry. Fébus’s painstakingly written Livre de la Chasse was, until the late 16th century, every hunting enthusiast’s bible. In addition, this well-written book with its accurate descriptions of nature and different kinds of animals, laid the foundations for a vast work on natural history that the acclaimed naturalist Georges Buffon (1707-1788) did not hesitate to use as the basis for his own Histoire naturelle used as a coursebook until the 19th century.

Of the forty-four extant copies of this manuscript, Français 616 is undeniably the most beautiful and complete. In addition to the Livre de la Chasse itself, this manuscript contains the Livre d’oraisons (a prayer books) also penned by Gaston Fébus, plus another treatise on hunting entitled Déduits de la chasse by Gace de la Buigne. Its pages are illustrated with 87 miniatures of outstanding quality that rank amongst the most attractive examples of early fifteenth-century Parisian illumination. Indeed, very few books teaching the art of hunting have such lavish illustrations on a par with those found in Bibles.

The lessons in the manuscript

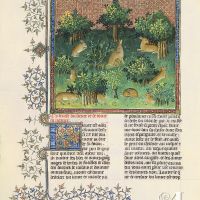

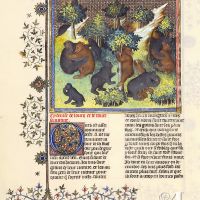

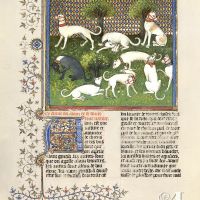

Until the late 16th century, the Livre de la Chasse was the hunting enthusiast’s bible, a eighty-five-chapter manual for hunters with a prologue and epilogue that describes in detail how to hunt successfully with hounds. Its text intended for young readers, combines the conciseness of a lesson with the keen interest of a man devoted to the subject. Gaston Fébus never belittles the importance of the animals involved in hunting, particularly the hound, the hunter’s faithful companion. Readers learn about the different breeds and their nature, how to train and feed them and even treat their illnesses, and discover that hunting – the preferred pastime of every medieval lord – involves a great many professional and human skills and qualities and is, therefore, far more than simply a leisure-time activity.

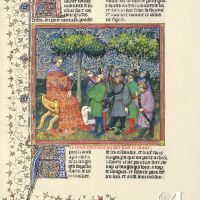

But if we focussed only on its technical content, we would miss the essence of Gaston Fébus’s book. Indeed, looking beyond the hunting context, this original and personal treatise is above all a child of its times, an era characterised by a pervading idea of sin and fear of damnation. In this book, Gaston Fébus presents hunting as an act of redemption enabling hunters to go straight to heaven. Being a physical activity requiring a certain expertise, hunting is indeed an excellent way of avoiding the idle hands for which the devil finds work, keeping the body and mind well occupied and thus avoiding all temptation. Hence this book is underpinned by tragedy of human existence and the quest for eternal life after one’s time on earth – to which only deserving souls can aspire.

Illustration

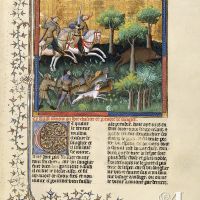

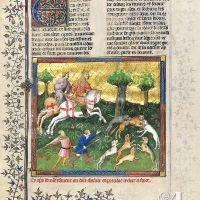

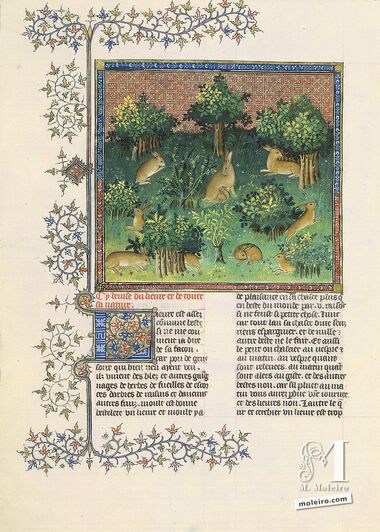

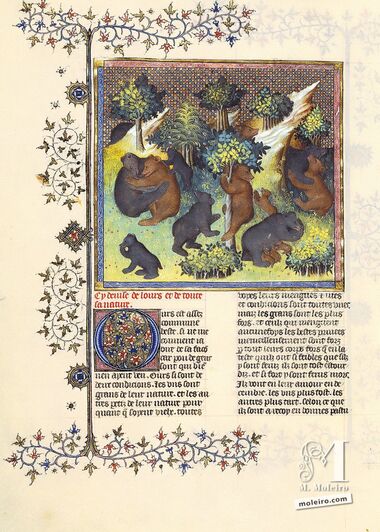

The miniatures are the work of several artists, particularly a group known as the Bedford school, amongst whom Master of the Adelphi stands out due to his keen eye and decorative style – factors that make his works exemplify International Gothic. One artist who collaborated with this group was the Egerton Master, whose style resembles that of the Limbourg brothers. Finally, some miniatures would seem to be the work of the Master of the Epistle of Othea, judging by the dense pictorial texture so very different from the smooth, porcelain-like technique of the Bedford school with which he seems to have collaborated only on this manuscript.

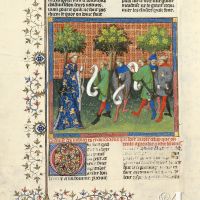

The illuminator uses his flawless mastery of the canons of medieval art to further the teaching aims of Gaston Fébus. The miniatures’ superbly decorated backgrounds are reminiscent of the tapestries of that period but on a smaller scale. The artist seeks not so much to portray an actual space as to highlight a hierarchy of values. Everything is calculated and designed within a coherent discourse. Hence the passage of time is suggested by the different ages of the figures, and their activities, relationships and spatial location, all of which draws a parallel between the hunting season and a lifetime of learning. The well-ordered and mimetic appearance of the elements portrayed are brimming with greatness and serenity, revealing to the reader a well-managed hunt, whilst providing not merely a hunting lesson but a lesson for life.

Hence this manuscript toys with analogy, a device typical of that period. Bodily parts are compared to planets, flowers to stars, and the earth to heaven. The world echoes itself time and time again. In addition, the proximity of persons and things combined with the dynamic lines of the miniatures convey the communication or echoes between them. Indeed, as the philosopher Michel Foucault explained, until the 16th century, the knowledge of the visible and invisible world, and the art of portraying and interpreting it, were based on likeness and repetition: the earth mirrors heaven, and art mirrors the world. In the specific case of the Livre de la Chasse, these elaborate analogies are reminiscent of the communication between hunters and their prey, thereby evoking the spiritual dimension of hunting, and the redemption and salvation it promises.