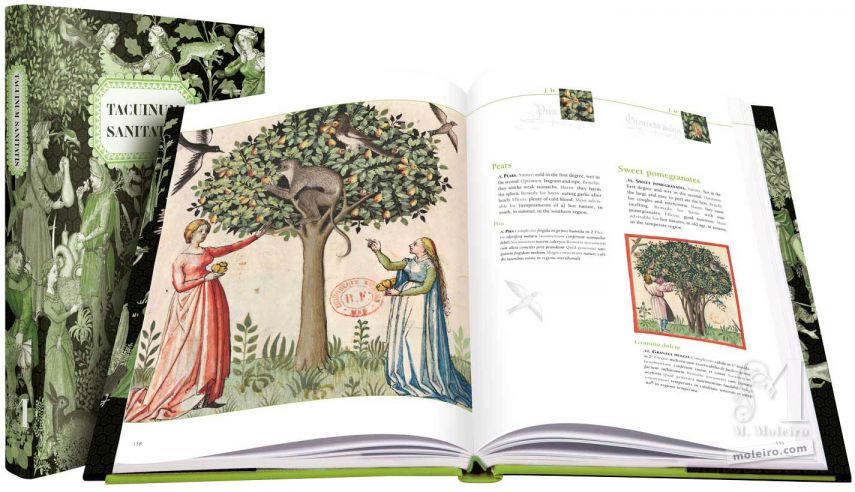

In the late Middle Ages, princes and the powerful learnt the health and hygiene rules of rational medicine from the Tacuinum Sanitatis, a treatise on well-being and health widely disseminated in the 14th and 15th centuries.

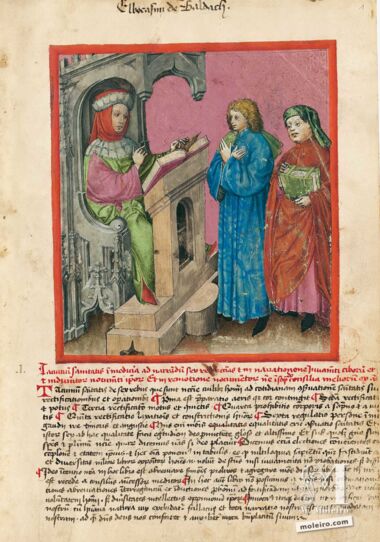

The treatise was written in Arabic by Ububchasym de Baldach, or Ibn Butlân as he was also known, a Christian physician born in Baghdad and who died in 1068. He sets forth the six elements necessary to maintain daily health and avoid being stressed: food and drink, air and the environment, activity and rest, sleep and wakefulness, secretions and excretions of humours, changes or states of mind (happiness, anger, shame, etc). According to Ibn Butlân, illnesses are the result of changes in the balance of some of these elements, therefore he recommended a life in harmony with nature in order to maintain or recover one’s health.

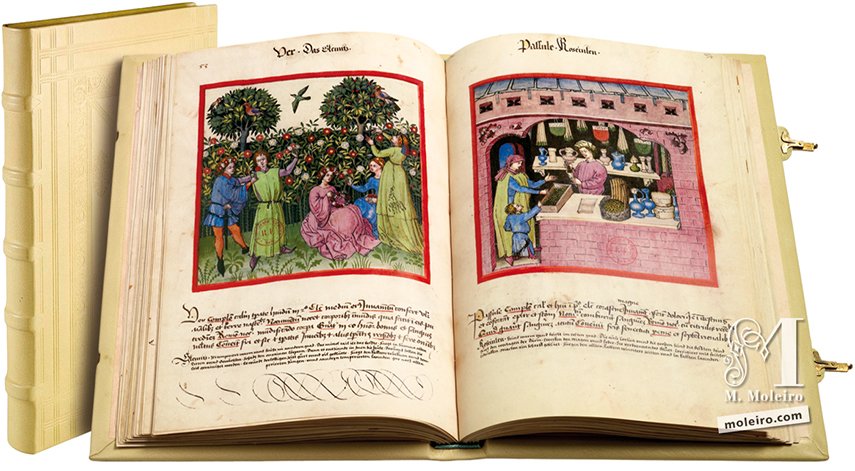

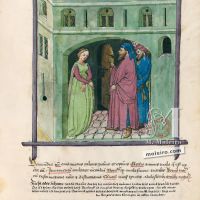

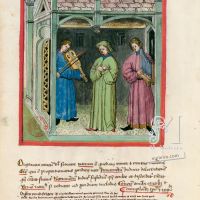

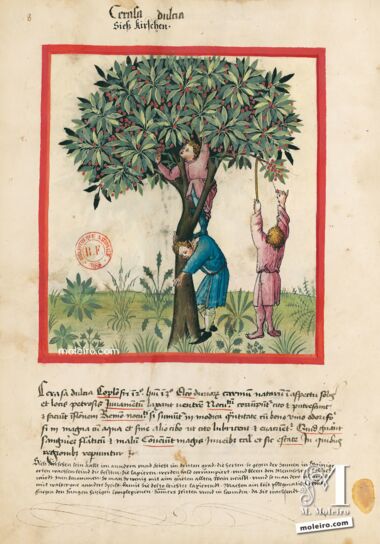

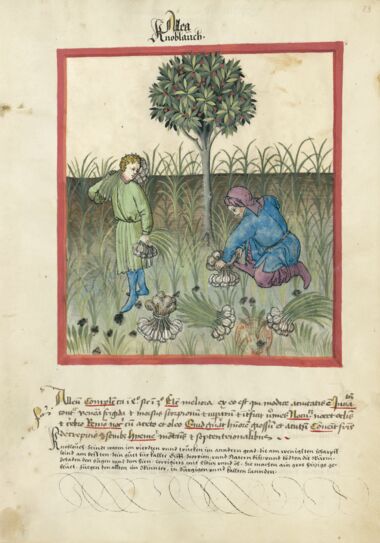

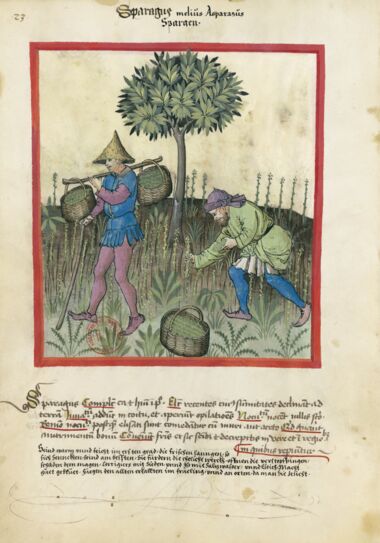

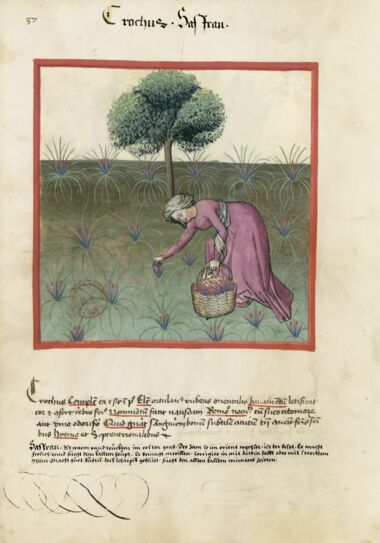

Ibn Butlân’s Taqwin al-sihha were translated into Latin in Palermo, at the court of Manfred, king of Sicily from 1258 to 1266, under the title of Tacuinum Sanitatis. In the late 14th century, in Lombardy, a highly developed series of illustrations was incorporated into this treatise, the starting point for a series of copies that spread beyond Italian frontiers, good evidence of which is this splendid codex made in Renania. Its every folio is illuminated with a miniature and a legend (in Latin, with a subsequent German translation) stating the nature of the element, the characteristics of what is deemed best for human health, its benefits, any harm it may cause and the remedy for such harm.

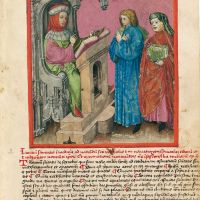

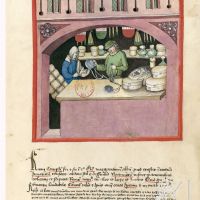

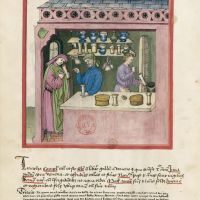

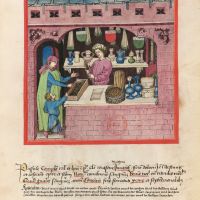

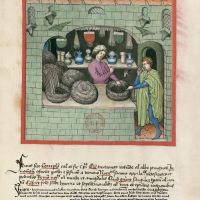

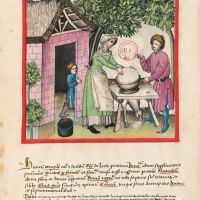

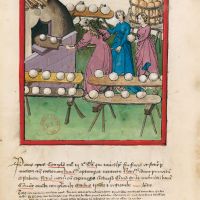

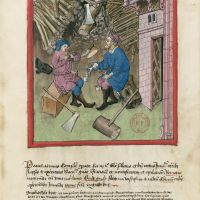

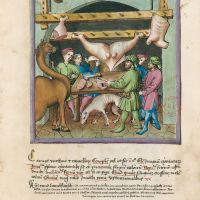

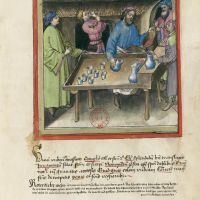

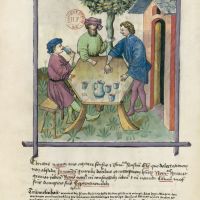

On sale at the confectioner’s, full of coloured vessels and shining glass jars, are delicious pine nuts with a spiced sugar coating, one of the sweets most popular in the Middle Ages. Also on sale are dried fruit and nuts, figs and raisins, particularly the “large raisins from Gerasa” that Ibn Butlân recommended old people eat in winter since “they are effective against intestinal pain, strengthen the liver and the stomach, and if they burn the blood, this can be remedied with lemon” (f. 54).

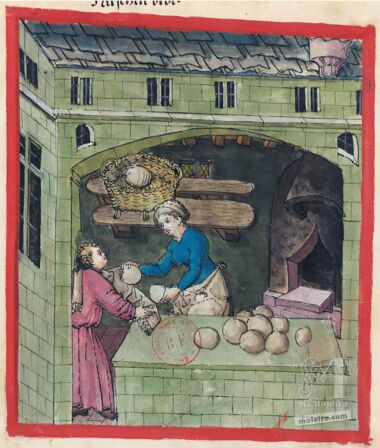

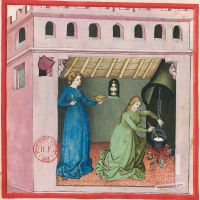

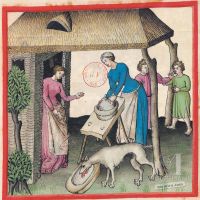

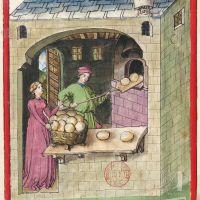

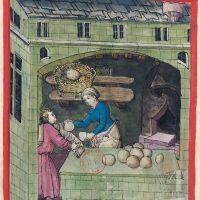

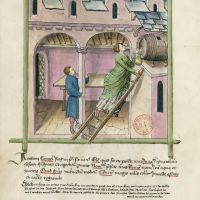

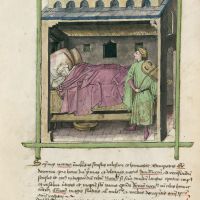

Ibn Butlân also recommended that brown bread be eaten because “it soothes the stomach, although, to prevent any irritation, it must be accompanied by greasy foods”. This is the most commonplace bread since white bread was reserved for the table of the most privileged. The miniaturist has painted three women, after preparing the dough, putting the loaves in the oven (f. 61v). Other miniatures depict cheese, pasta and butter being made; merchants of salt, birds and almond oil; and vendors of salted meat, candles, silk fabrics, etc.

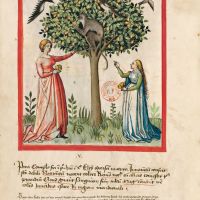

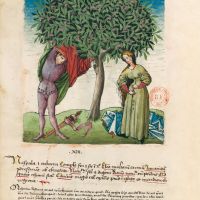

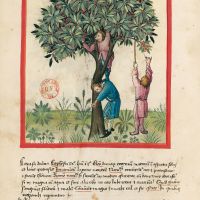

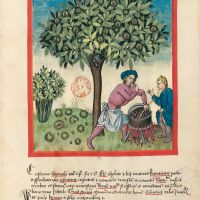

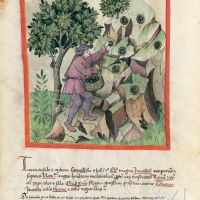

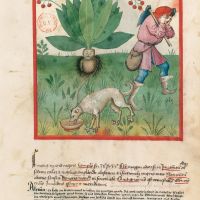

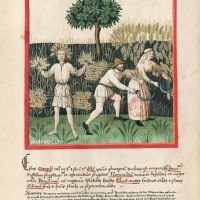

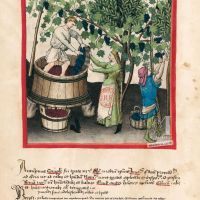

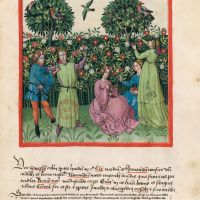

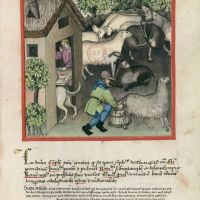

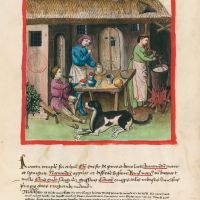

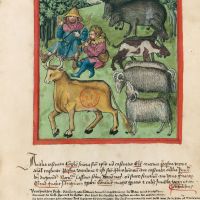

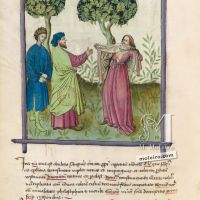

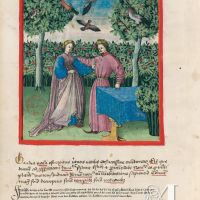

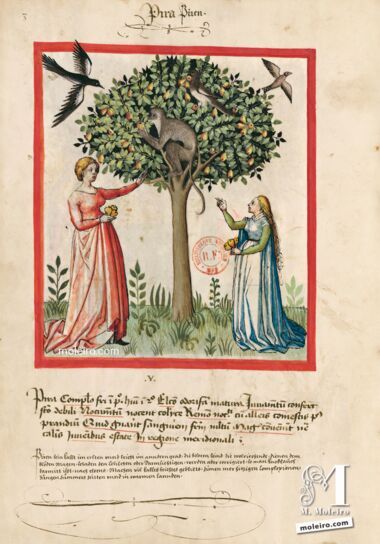

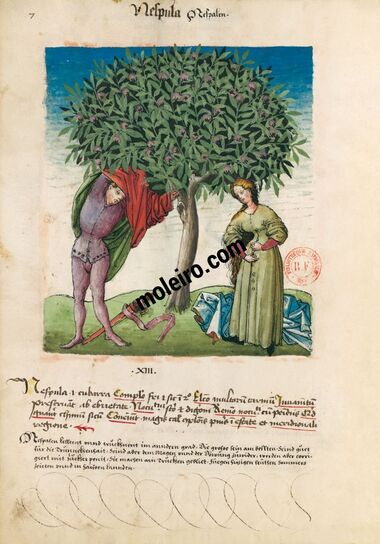

Harvests of cherries, pomegranates, apricots, walnuts, chestnuts and countless other fruits and vegetables occupy many of the folios in these tables of health explaining the beneficial and harmful effects of each element.

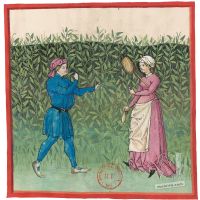

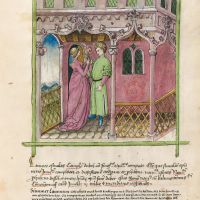

Ibn Butlân also teaches us to enjoy each season of the year, the consequences of each type of climate, wind and snow. He points out the importance of spiritual wellbeing and mentions, for example, the benefits of listening to music, dancing or having a pleasant conversation.

According to the coat of arms at the beginning of the codex (f. Dv), added shortly after it was made, this beautiful manuscript belonged to Count Louis of Wurtemberg and his wife, Matilda, the daughter of Louis of Baviera, the Palatine count of Renania.

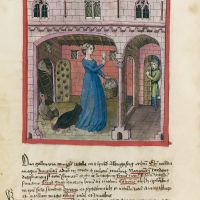

This codex is not only an interesting source of medical information and anti-aging remedies, but also a remarkable iconographic source for the study of every-day life in the Middle Ages.

_7.jpg)